OSIRIS-REx / OSIRIS-APEX

Overview

The Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security – Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission was launched on September 8, 2016. OSIRIS-REx is NASA’s first asteroid sample return mission. It collected a sample from the asteroid (101955) Bennu on October 20, 2020 and successfully returned the sample to Earth on September 24, 2023 by deploying a sample return capsule. The spacecraft then continued on to a new asteroid target, (99942) Apophis, which it will reach in 2029.

Artist’s conception of the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft collecting a sample from Bennu (Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona).

Artist’s conception of the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft collecting a sample from Bennu (Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona).

This extended mission, renamed as OSIRIS-Apophis Explorer (OSIRIS-APEX), will rendezvous with Apophis in April 2029. It will study the physical changes to Apophis after its rare close encounter with Earth, at a distance of ~32,000 km from Earth’s surface, less than 1/10 the lunar distance. The OSIRIS-APEX spaceraft is currently expected to stay at the asteroid for science operations for 18 months, starting from Apophis orbit insertion in August 2029 up to spacecraft passivation in January 2031.

Artist’s conception of the OSIRIS-APEX spacecraft at Apophis (Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona).

Artist’s conception of the OSIRIS-APEX spacecraft at Apophis (Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona).

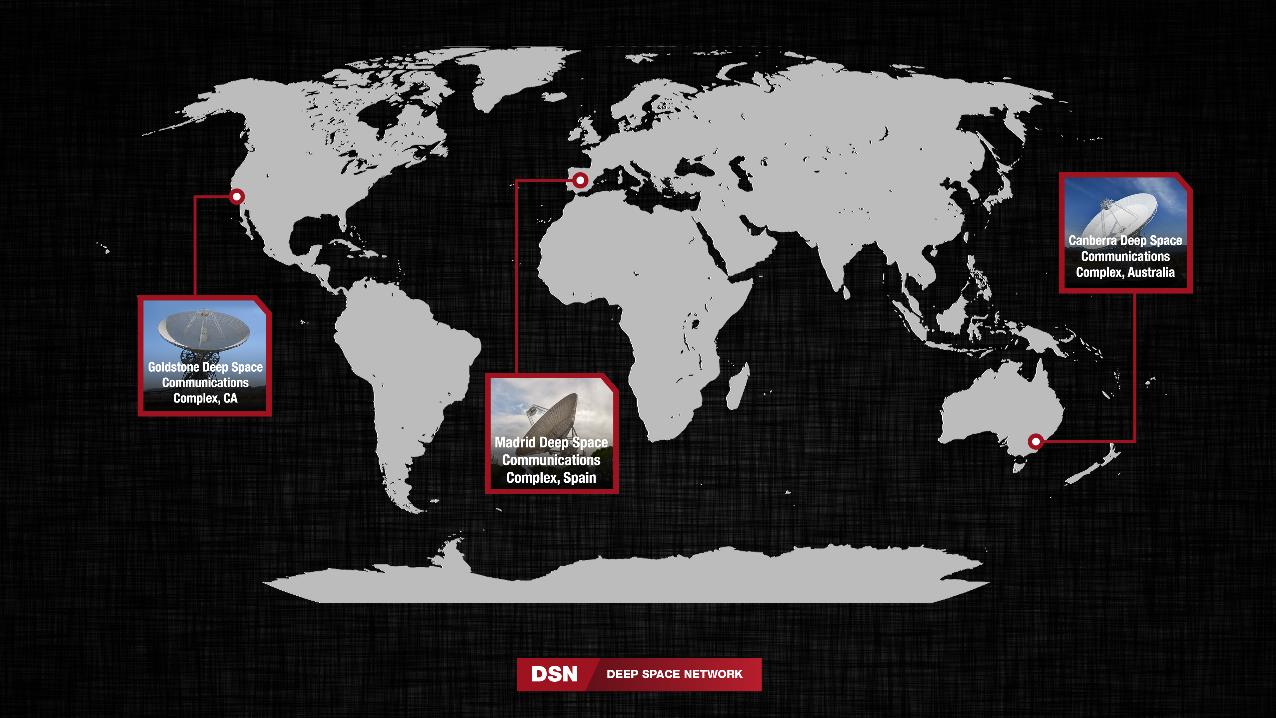

The Deep Space Network

The Deep Space Network (DSN) is an array of massive radio communication antennas used by NASA to support its interplanetary spacecraft missions, plus a few that orbit Earth. The DSN also provides radar and radio astronomy observations that improve our understanding of the solar system. It consists of three radio telescope facilities located near Barstow, California; Madrid, Spain; and Canberra, Australia. These sites are located approximately 120 degrees apart in longitude, which provides full coverage of the sky above 15 degrees elevation. The DSN is operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which in turn is managed by the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

The Deep Space Network facilities around the world (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech).

The Deep Space Network facilities around the world (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech).

My Work

Because the DSN supports all of NASA’s interplanetary missions (as well as some missions managed by other agancies across the globe), the demand for DSN time for any current mission is extremely high. Due to this, the DSN is heavily over-subscribed, and it is not possible to schedule all of the requested time for every mission.

In the summer of 2022, I interned for some members of the OSIRIS-REx flight dynamics team at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC). I worked on a project to determine whether the imaging instruments aboard the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft could be used to help spacecraft figure out where it is in space. This is called Optical Navigation (OpNav), and it is a technique that has been used on many missions, including OSIRIS-REx during its time at Bennu.

However, using OpNav for Celestial Navigation (CelNav) is not something that has been used as the primary method for navigating a spaceraft before. The idea was that if we could assess the feasibility and performance of CelNav, we could potentially do a technology demonstration during the OSIRIS-APEX mission’s cruise phase. I need to emphasize that this was a preliminary study, and there are no concrete plans of using this method to navigate the OSIRIS-APEX spacecraft.

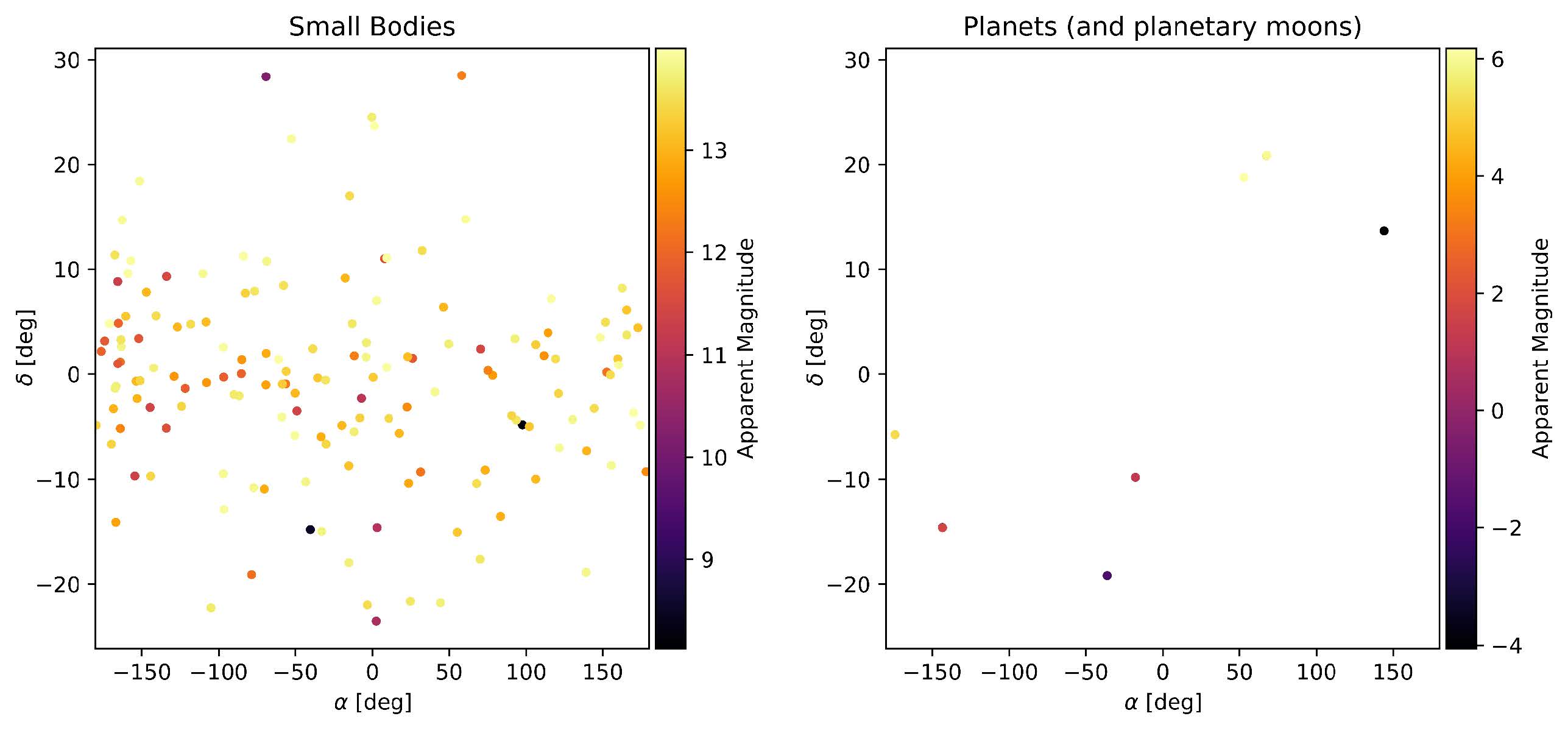

The way I studied this was by propagating ~8,000 solar system objects including the planets, some moons, as well as small bodies such as asteroids and comets through the duration of the OSIRIS-APEX cruise phase. Then I computed the apparent magnitudes of these objects as seen from the spacecraft to determine if they would be visible to the onboard instruments. The below figure shows the apparent magnitudes of all the bodies in right ascension ($\alpha$) and declination ($\delta$) space.

Apparent magnitudes of solar system objects as seen from the OSIRIS-APEX spacecraft during cruise. The colorbar indicates the apparent magnitude of the objects.

Apparent magnitudes of solar system objects as seen from the OSIRIS-APEX spacecraft during cruise. The colorbar indicates the apparent magnitude of the objects.

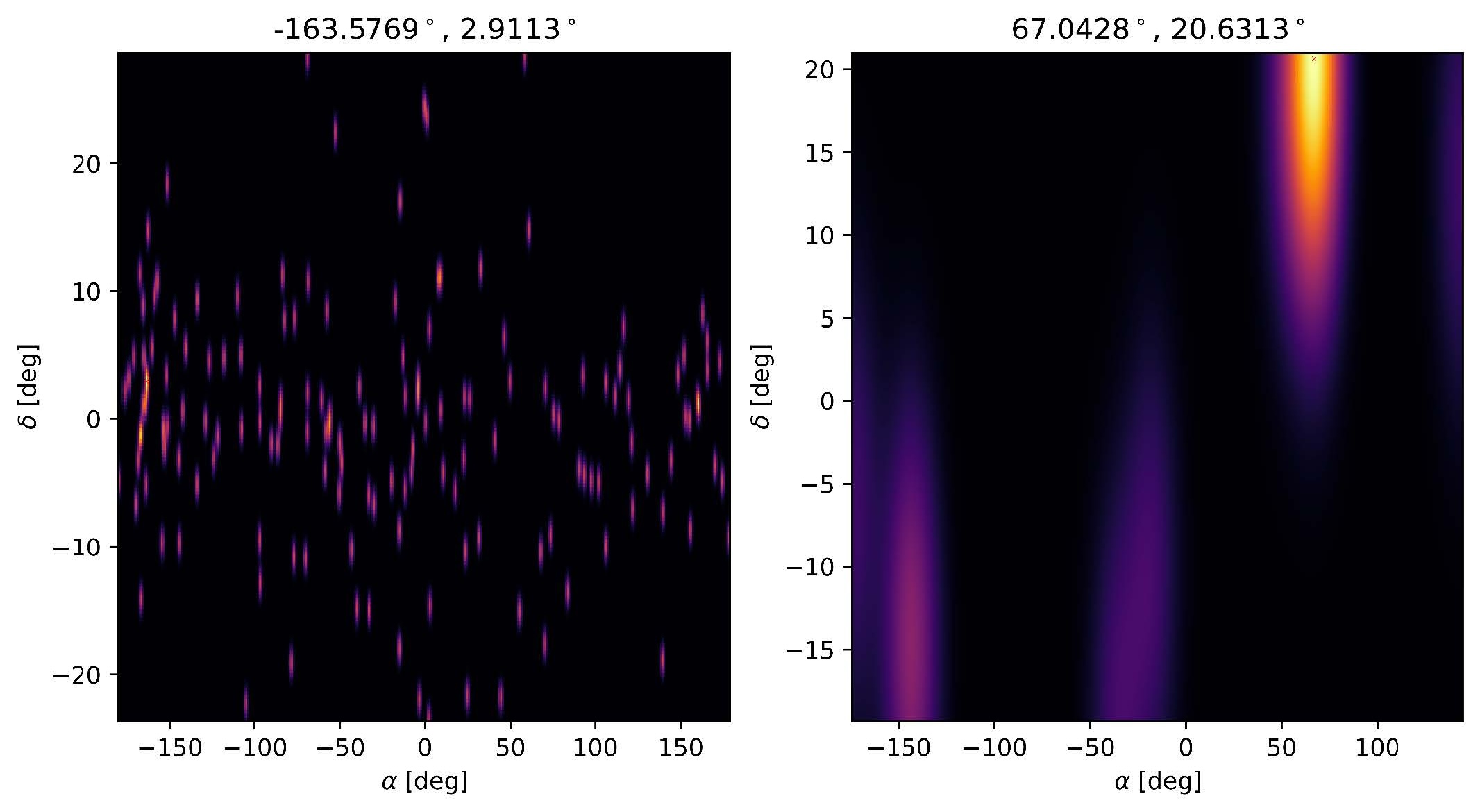

However, the spacecraft cannot look at all these objects at once. It can only look at those objects that are in its field of view for a given ($\alpha$, $\delta$) coordinate to point the center of the intrument’s field of view at. Therefore, we need to determine the best place to point for a given time. I did this by assigning a 2-dimensional gaussian distribution to each object. I chose the standard deviation of the gaussian to be the camera’s field of view, and the mean to be the center of the object. Then I summed all the gaussians to get a “heat map” of where the spacecraft should point at a given time. The below figure shows one such heat map. The title of the subplots give the optimal pointing for the spacecraft at that time for the given object type.

Heat map of where the spacecraft should point at a given time. The same type of heat map is shown for small bodies (left) and planets and moons (right).

Heat map of where the spacecraft should point at a given time. The same type of heat map is shown for small bodies (left) and planets and moons (right).

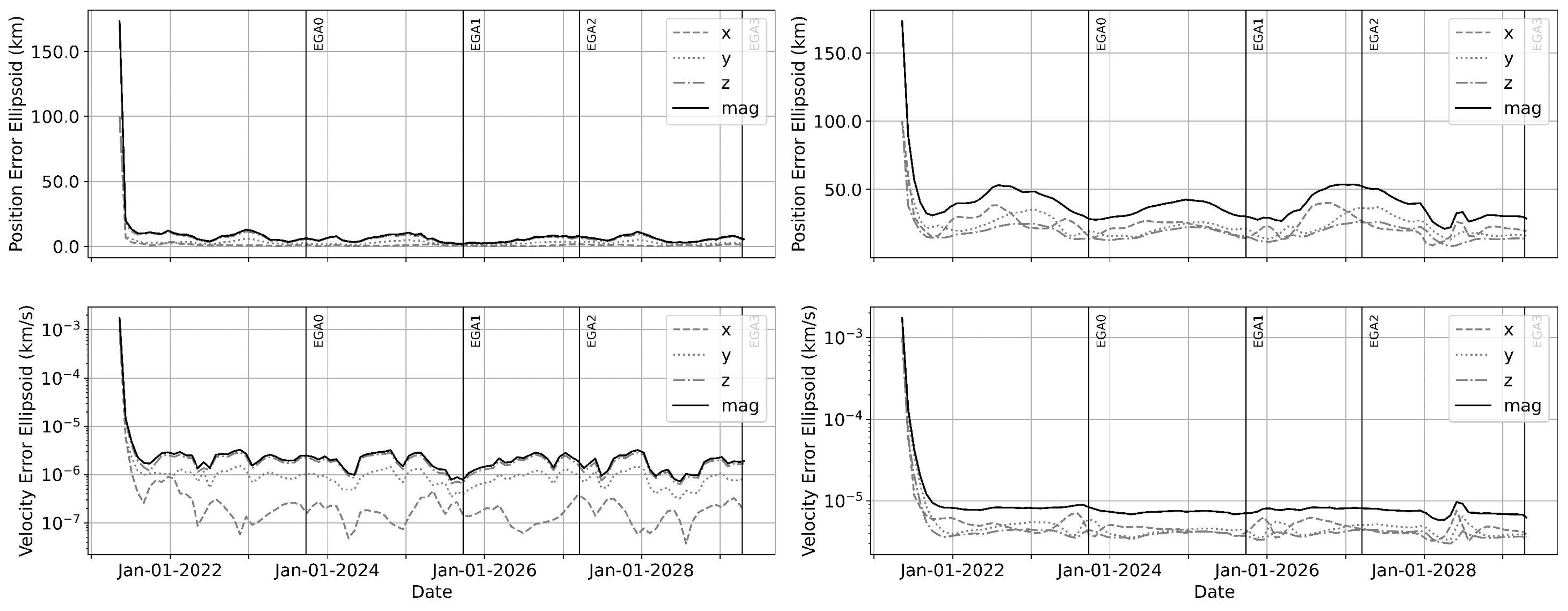

We can then conduct spacecraft covariance analyses with optical measurements from the visible objects at a given time. The below plot shows the uncertainties in the spacecraft’s position and velocity as a function of time. The left plot shows the uncertainties for a radio-only campaign that uses the DSN to track the spacecraft. The right plot shows the uncertainties for an optical-only campaign that uses the spacecraft’s onboard instruments to track the spacecraft.

Uncertainties in the spacecraft’s position and velocity components and magnitude as a function of time for a DSN-only campaign (left) and an optical-only campaign (right).

Uncertainties in the spacecraft’s position and velocity components and magnitude as a function of time for a DSN-only campaign (left) and an optical-only campaign (right).

Therefore, these initial results showed that only using optical measurements for navigating a spacecraft seems to give reasonable uncertainties for the spacecraft state. Therefore, it is possible for future missions to maybe use optical CelNav during non-mission critical phases of a spacecraft’s lifetime (such as interplanetary cruise) and only switching to the more expensive DSN tracking passes during critical phases (such as gravity assists).

Therefore, this optical CelNav approach is useful in the context of deep space navigation. Furthermore, results also demonstrate the incentive of improving the optical imaging hardware to reduce noise in the produced images. In this improved hardware case, the final uncertainty using optical measurements alone was comparable to and could potentially replace a DSN radio measurement-only operations plan. The advantage of these results is that such a concept of operations could potentially eliminate, if not significantly reduce the demand on the already over-subscribed DSN while delivering similar information about the uncertainty surrounding the spacecraft state.